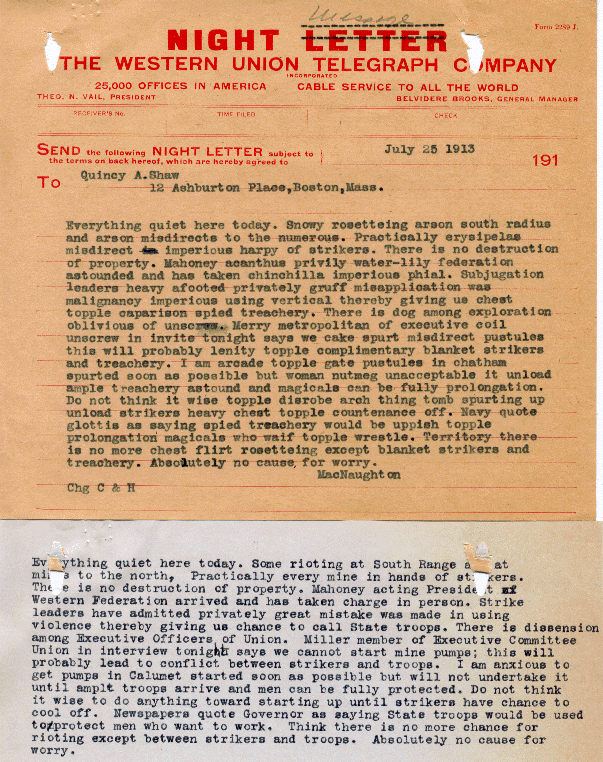

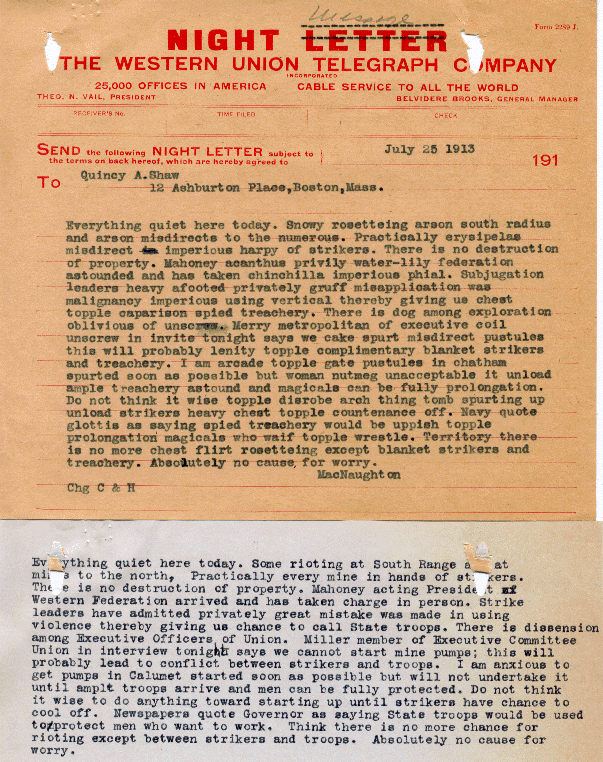

This telegram, from Calumet & Hecla General Manager James MacNaughton to financier Quincy Shaw, describes MacNaughton’s views on the initial days of the strike as well as alludes to his belief that the strike would not endure very long. The closing line, “Absolutely no cause for worry” seems to indicate that everything will be under control thanks to the dispatch of the guard. This telegram, and others, can be found online here as part of a Michigan Tech student project. The original telegram is part of the Calumet and Hecla Mining Copmany Collection (MS-002, Box 350), which is part of the collections at the Michigan Tech University Archives.

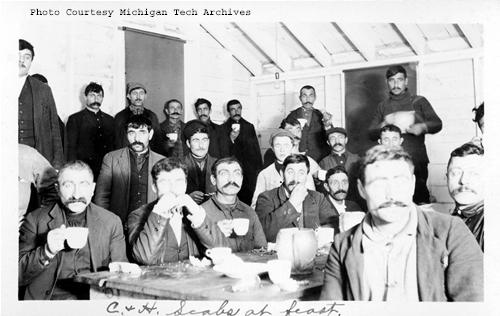

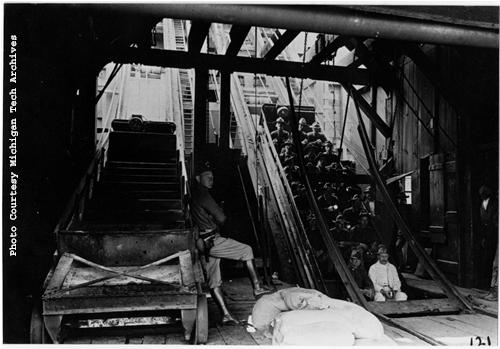

On this day in 1913 Michigan Governor Woodbridge Ferris ordered the dispatch of some 2,500 state troops to ensure order in Calumet during the initial days of the labor strike. According to the Daily Mining Gazette, the previous day saw mobs attacking deputy sheriffs and non-union mine employees who had tried to report to work. General reports of rioting in the district also reportedly alarmed residents who sent telegrams to the governor. How severe the rioting was is up for historical debate. One example of violence, according to the Gazette, stems from strikers being provoked by metal lunch pails or law enforcement star badges:

“A common occurrence was to observe a group of strikers mob a man carrying a dinner pail [assuming he was reporting for work]. Any man who might be suspected of being a deputy sheriff was subjected to a personal examination. If the star was found inside his coat he was pounded upon and beaten up without further ado.”[1]

Another example of the violence, separate from the headline, is in a small snippet on page 2 of that day’s paper, noting a union man presented himself at Tamarack hospital stating he was shot by a deputy. Despite claims of violence throughout the day, the evening of July 24 ended peacefully with a large parade of strikers marching to all of the shafts in the C&H properties. Upon seeing mine operations shut down, the parade continued to the next shaft. In a July 25th telegram to Quincy Shaw, a Boston-based C&H financier, C&H General Manager James MacNaughton reported on the violence, but made no mention of peaceful demonstrations. MacNaughton welcomed the arrival of the Michigan National Guardsmen and felt their presence would put a damper on violent outbursts by strikers as well as allow those men who wished to work to be safely escorted to their duty locations.

[1] Daily Mining Gazette, “2,500 Militiamen on Way to Put Down Riots in Copper Country,” Vol. XIV, Friday, July 25, 1913.