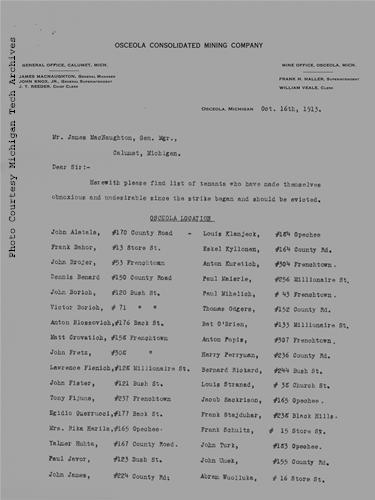

This is the first page of the letter urging the eviction of men living in company housing but supporting the strike that Haller sent to MacNaughton on this day in October 1913. (Photo is courtesy of the Michigan Tech Archives, Keweenaw Digital Archive)

On this day in the strike Frank Haller, superintendent of the Osceola Consolidated Mining Company, sent the above letter to James MacNaughton, General Manager of the Calumet & Hecla Mining Company, the firm that owned Osceola Consolidated. The letter is a list of men from the Osceola mine location who were living in company housing while participating in the strike. Haller urges MacNaughton to evict the strikers: “Herewith please find lists of tenants who have made themselves obnoxious and undesirable since the strike began and should be evicted.” A second page of the letter says “there are others at each location who are not working and may have to be evicted later; it would be well to start action on this list as soon as possible.”