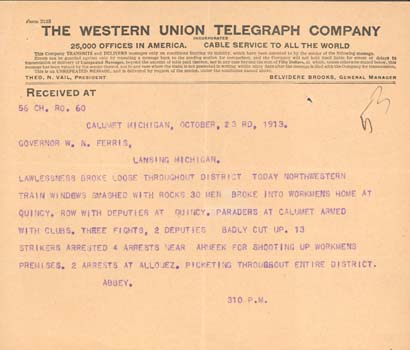

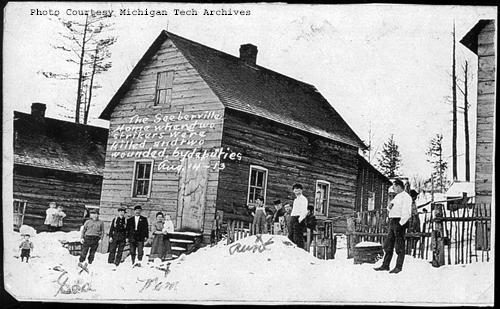

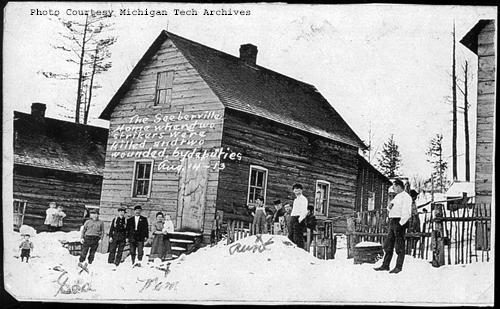

View of the home in Seeberville, MI where Steve Putrich and Louis Tijan were killed. The Putrich boardinghouse, at #17 Second Street in Seeberville, was rented from the Copper Range Mining Company. Joseph and Antonia Putrich lived in the home with their children, relatives, and boarders. In the photo the labels indicate “Dad” (Joseph Putrich), “Mom,” (Antonia Putrich), “Aunt,” (Josephine (Grubesich) Tijan), and the others are likely their children, boarders, and/or other relatives. (Photo Courtesy of the Michigan Tech Archives, Keweenaw Digital Archives)

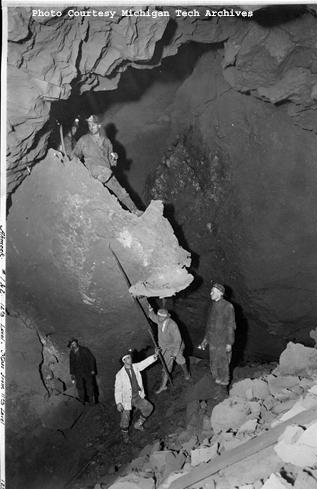

On this day in the strike a seemingly regular day ended in tragedy as a boardinghouse in Seeberville was shot up by deputies. On the morning of August 14, 1913 a group of strikers from Seeberville, a residential community of mine homes south of Painesdale, walked a few miles to collect their striker benefits from the WFM office in South Range. The men enjoyed some beer and conversation before they headed home. On the walk back the group separated and two men decided to cut across mine company property to take a shortcut, even though it was off limits due to the strike. Upon entering the company property they were confronted by the company watchman. A few words were exchanged, but the two strikers continued on home to Seeberville.

Upon arriving in Seeberville the two who took the shortcut met up with their other fellows from the boardinghouse, had supper, and enjoyed some ninepin on the front lawn. In the midst of their game, deputies came to the yard and attempted to arrest one of the men who took the shortcut through company property. John Kalan resisted arrest and went into the house along with his fellow boarders. Just as the deputies were about to leave, one of the boarders took a bowling pin and threw it at a deputy’s head. Without hesitation that deputy drew his gun and fired, with the remaining deputies joining in to fire into the house. Two men, Steve Putrich and Alois (Louis) Tijan, were killed and two others were wounded. None of the men in the house were armed and the men who were hurt and killed were not involved in the incident at company property earlier in the day. One witness reported that the men “didn’t have anything to shoot with except the spoons they had in their hands while they were eating,” illustrating that the hail of bullets was an unwarranted response to a thrown bowling pin.[1] This tragedy is a prominent example of strike violence escalating quickly with horrific results. The Seeberville murders by their very shocking nature had a huge impact on the public at the time of the incident and they have also had a prominent part in the story of the strike.

For a unique perspective on the events and context of the Seeberville tragedy please see Alison Hoaglan’s article “The Seeberville Murders: Death and Life in the Copper Country in 1913,” available as a chapter in New Perspectives on Michigan’s Copper Country (2007). She not only discusses the events of the tragedy but also paints a picture of immigrant life and the company town, using the Seeberville murders and another incident, the Dally-Jane murders which took place four months later, as examples.

[1] Testimony of Antonia Putrich, Agust 22, 1913, The People vs. Thomas Raleigh, Edwin Polkinhorne, Harry James, Joshua Cooper, William Groff, and Arthur Davis, Houghton County Circuit Court Case #4230.

[2] Alison K. Hoagland, Erik C. Nordberg, and Terry S. Reynolds, eds. New Perspectives on Michigan’s Copper Country. Hancock, MI: Quincy Mine Hoist Association, 2007, 115-132.